Motivation is such a crucial part of learning and task performance, and yet, it remains one of the great mysteries to educators, students, and parents alike. “I don’t feel like it,” is a constant refrain, and procrastination is rife. Why is this, and what can we do about it?

Self-determination theory places motivation on a spectrum ranging from extrinsic to intrinsic. If our desire is to see students becoming fruitful and independent, our goal will be to get students to become less reliant on external stimuli and more reliant on their own internal drive, in order to act out desirable behaviours. There are certain supporting conditions that enhance intrinsic motivation. This article, based on Ryan and Deci’s self-determination theory, defines the opposite ends of the motivation spectrum and the environmental situations that develop intrinsic motivation.

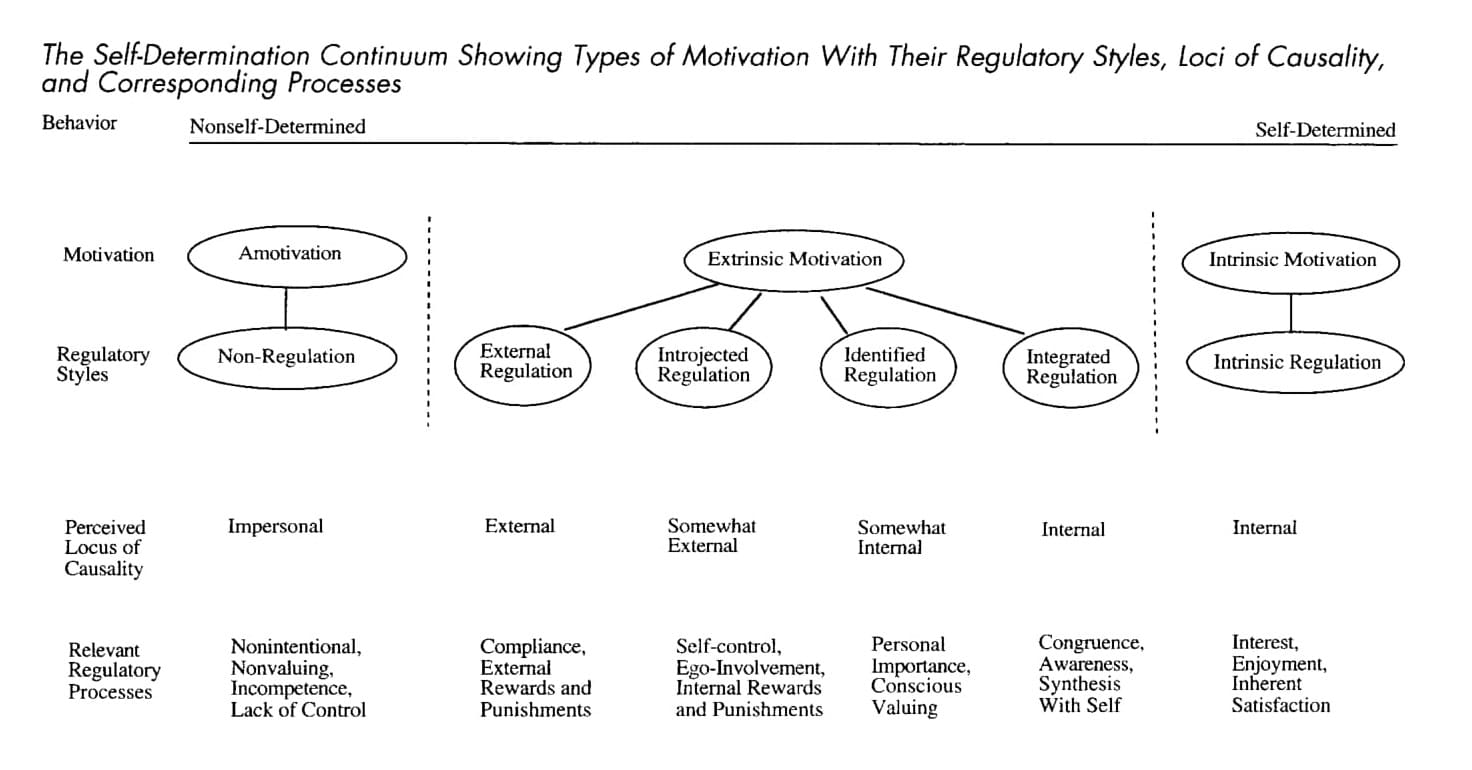

Motivation, according to Ryan and Deci’s Self-determination theory (SDT, 2000) can be seen to exist on a spectrum between entirely externally regulated and entirely internally regulated; exterior to this is the concept of A-motivation (where no motivation is present whatsoever and there is no control of the activity coming from any source interior or exterior to the subject).

External Motivation

Externally regulated motivation is motivation that comes from fear of punishment or from the expectation of a reward. It gets things done, but we don’t want students to stay in this space. When a task is performed from the place of external regulation, creativity and inspiration are diminished. Further to this, if a person cannot internalise motivation to perform a task, the person becomes entirely dependent on outside forces to propel him or herself to action.

While it is tempting to keep students in a place where the educator or parent maintains absolute control, it is ultimately detrimental to the development of autonomy and self-regulated motivation of the individual. Often this is seen as a last resort out of worry for the welfare of the student, or as Stephen Covey notes in the opening chapters of his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, it can be in response to a desire to have one’s parenting affirmed. In the second instance, the behaviour of the child is controlled by the adult not out of a desire for the child’s identity and competence to be affirmed, but out of a necessity for the adult’s reputation to be upheld.

Internal Motivation

Internal regulation, or intrinsic motivation, however; is “the inherent tendency to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise one’s capacities, to explore, and to learn” (Ryan & Deci, 2000:70). This phenomenon is the natural tendency of the human mind – the “inclination toward assimilation, mastery, spontaneous interest, and exploration that is so essential to cognitive and social development and that represents a principal source of enjoyment and vitality throughout life”.

When individuals are intrinsically motivated, they perform a task for the sheer enjoyment of it; they learn without being coerced. It is discovery, play, and this state of enjoyment that bolsters the individual’s efforts, even in the face of adversity. This is the sort of motivation that we long for as individuals, and we long to see in our students and in the children in our care. It is not enough to nag and to nag without seeing results; our very natural desire is to be moved to act and overcome challenges in a state of ‘flow’ – to be utterly absorbed by the activity. Unfortunately, we do not always have the time for inspiration to strike before the work needs to be handed in. We cannot simply wait to feel the positive emotion required to ‘get stuff done’.

On a side note, positive emotion can greatly assist in the solving of structured problems, but, perhaps unexpectedly, negative emotional states assist in deeper research and systematic approaches to problems . The next time you or your students get in a funk, it might be time to reframe the experience and look at the task as an opportunity to practise strategic and systematic learning.

How then do we, as the ‘adults in the room’, foster intrinsic motivation in ourselves as well as in the children in our care?

According to Ryan and Deci, who developed Self-determination theory (2000), there are certain tried and tested conditions that support the internalisation of regulation. In other words, there are factors that need to be present which move one’s motivation from the external side of the spectrum to the internal side. These conditions are: Relatedness, Competence and Autonomy.

(Ryan & Deci, 2000:72)

Relatedness

First and foremost, the individual needs to be in an environment in which he or she does not feel isolated. Positive relationships with others – peers, teachers, and parents – are a crucial part of fostering the internalising of motivation. One of the reasons for this is that desirable behaviours are formed as a result of modelling. In other words, individuals copy people they like.

My 18-month-old niece, for example, has begun sweeping the house and wiping up spills, not because any of her family members have told her to do so but because she has seen the behaviour modelled by those with whom she holds a positive relationship. While this is anecdotal evidence, it serves to prove the importance of Relatedness. It is highly unlikely that an infant would perform such a behaviour with such joy if it were not as a result of intrinsic motivation based on the principle supporting condition of Relatedness.

When we see those who we hold in high esteem working hard, it instils the same desire in us. The reverse, therefore, is equally possible. This goes to confirm the old adage, “bad company corrupts good morals” and is a good reminder to associate ourselves with those people by whom we are inspired.

This idea of Relatedness also reminds me of a story I once heard told by Jordan Peterson. A friend, highly successful in his own right, confided in him that he struggled with a deep-seated feeling of inadequacy and when probed the man explained that he had been comparing himself to his college roommate. The college roommate? Elon Musk.

We become like the people we associate with, and a positive trend toward the internalisation of motivation is fostered by forming positive relationships with people whose behaviour we desire to emulate. This is Relatedness.

Competence

The second supportive condition of internalised regulation in intrinsically motivated people is competence. Individuals need to feel capable of performing the task set before them. This means two things.

Firstly, the task should be at the level of ‘optimum challenge’. This is to say that the task should not be so hard that it appears impossible and overwhelming to the student, nor should it be so easy that its achievement is not commendable.

Secondly, the condition of competence can be supported by effective feedback. If the individual’s behaviour is not validated, it is difficult to evaluate whether or not he or she is performing the task satisfactorily; additionally, Relatedness is thwarted.

Competence is also evaluated in comparison with other successful attempts at the task. It can be auto evaluated or evaluated by the educator, parent or peer. In auto-evaluation, the student compares him or herself with what he or she perceives to be correct. In feedback-driven evaluation, the student’s competence is appraised by another person. It is obvious then, that feedback should be positively framed as a guiding process and not as a conclusive result.

“You have done X & Y part of the problem correctly, but your approach to the final part is incorrect and it can be better achieved like this…” is a positive approach to unsuccessful task performance as it fosters the child’s feelings of competence rather than a simple, “Your answer is wrong,” or, “My daughter is bad at maths, can you help her?”.

Autonomy

Finally, autonomy is the third supporting condition of self-regulated motivation.

It is, surprisingly, even more important than competence. Furthermore, while it may seem obvious that the fear of punishment would negatively influence motivation to perform a task, the presence of rewards also diminishes intrinsic motivation. This is because both punishment and rewards change the perceived locus of control of the action.

This means that instead of the joy of the activity coming from the performance of the task itself, the action is being controlled externally by the giver of the reward. Put another way: Xoliswa reads books in French for her own personal enjoyment, she enjoys the challenge, and she likes the stories, but when her teacher starts to give her bonus marks in class for the activity, she can’t explain why but she begins to feel that she is reading the books for her teacher and not for herself.

Rewards such as praise and good marks are a positive and essential part of good school performance, but in order for intrinsic motivation to be fostered in students, which will take them far beyond their school experience, they also need to be given freedom of choice and direction in order to have a sense of autonomy. They need to feel that certain of their actions are self-directed and that they are responsible for their own successes.

Of course, autonomy must be related to the age and ability of the child. There are decisions that it is only natural an adult caregiver should be making for the child.

Conclusion

Motivation is still for the most part an unknown. It is still almost impossible for the human mind to pinpoint exactly from where interest in a specific field is derived or why certain goals are upheld. We can, however; as individuals, educators and caregivers foster the internalisation of our own and our students’ motivation in order to enhance our own and their fruitfulness in work and play. This can be done through the development of Relatedness (providing and encouraging positive relationships), competence (enhancing the feeling of capability) and autonomy (promoting free choice and creativity where suitable to enhance the perception of an internal locus of control).

For practical guidance on how to leverage these principles to increase motivation in ourselves and our children, see Carmen’s article on how to do just that.

Bibliography

- Cherry, K., 2021. The Psychology of Flow. [https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-flow-2794768] Accessed 06 August 2021.

- Baars, M., Wijnia, L. & Paas, F., 2017. The Association between Motivation, Affect, and Self-regulated Learning When Solving Problems. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(1346), pp. 1-12.

- Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L., 2000. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist, 55(1), pp. 68-78